Strange to reflect that there was a period in the seventies, when a copy of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet was obligatory on every student’s bookshelf. Now he seems as passé an emblem of the era as that poster of the female tennis player scratching her fulsome bare cheek.

I recently introduced a passage from Reflections on a Marine Venus to a writing group and was highly embarrassed as they analysed its multiple deficiencies to oblivion. How could I not have seen them? The lushness of colour, the elaborate, sometimes creaking imagery –’In the fragile membranes of light which separate like yolks upon the cold meniscus of the sea’ – and the metaphors piled on top of one another and so little substance to underpin them. The truth is I think I have always seen them and always forgiven them

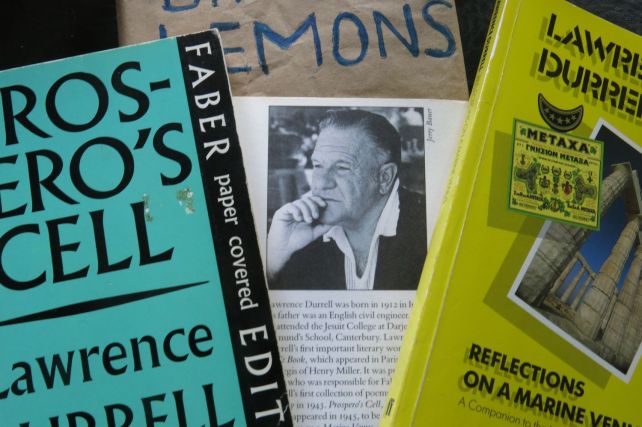

They are the kinds of failings intrinsic to a writer with undeniably acute powers of observation, yet one given to writing very quickly. Apparently 4,000 words a day was by no means exceptional for Durrell. And I still maintain that even Reflections, an account of his post-war period on Rhodes, contains some truly wonderful writing and superb characterisation. I also think that the trilogy on Greek islands – Prospero’s Cell (1945), Reflections (1953) and Bitter Lemons (1957) – stands the test of time. All three are still in print and by Mark Twain’s measure of literary immortality (‘about thirty-five years’) Durrell’s trio are classics indeed.

During a visit to Northern Cyprus earlier this month Maria and I were able to make pilgrimage to the central locus for what is unquestionably the finest of them, Bitter Lemons. Bellapaix is just a short drive to the east and slightly landward from the port of Kyrenia.

(HERE’S MARIA OUTSIDE THE HOUSE THAT WAS BUILT IN 1897 AND WHICH DURRELL BOUGHT IN 1953 for £200. HIS DESCRIPTION OF ITS PURCHASE IS ONE OF THE GREAT COMIC MOMENTS OF THE BOOK. THE VIEWS FROM ITS UPPER BALCONY ARE SUBLIME: ‘FROM THIS HIGH POINT WE WERE ACTUALLY LOOKING DOWN UPON BELLAPAIX, AND BEYOND IT, FIVE MILES AWAY, UPON KYRENIA WHOSE CASTLE LOOKED ABSURDLY LIKE A TOY.‘)

Today the village makes much of Durrell. The local cafe overlooking the Abbey of Bellapaix is called the ‘Tree of Idleness’, which is a name for one of his chapters. There was apparently a real tree (unusual for Durrell, he never identified the species but I guess it would have been a plane), whose cool-spreading foliage was the location for many of the book’s reported conversations.

(‘AND THE ABBEY ITSELF WAS THERE, FADING IN THE LAST MAGNETIC FLUSH FROM THE HORIZON, WITH ITS QUIET GROUPS OF COFFEE-DRINKERS AND CARD PLAYERS UNDER THE TREE OF IDLENESS. AT FULL MOON WE DINED THERE, BAREFOOTED ON THE DARK GRASS, TO WATCH THE LIGHTS WINKING AWAY ALONG THE FRETTED COAST …’)

In the way that life often imitates art, the road on which Durrell’s old house stands is now called Aci Limon Sokak, ‘Bitter Lemon Street’. When its current occupants are in town they apparently open it to the public and give Durrell-inflected presentations. It is a lovely looking property, although it was not actually where he wrote Bitter Lemons (I learn from his volume of diary and occasional writings called Spirit of Place), he completed it during a brief stay in Dorset. But he did write Justine in Bellapaix, the first of the Alexandria Quartet. He would rise pre-dawn, so he said, to get the words down before the day came crowding in; then he would set off over the Kyrenia Range to teach in Nicosia.

(MY HERO FOR THE TRIP WAS THIS CYPRESS, NEAR TO BUFFAVENTO IN THE KYRENIA RANGE, WHICH HAD PROBABLY BEEN GROWING IN THIS EXTRAORDINARY POSITION SINCE BEFORE DURRELL EVER SET EYES ON THE ISLAND. ITS DAILY VIEW INCLUDES TURKEY AND THE WHOLE OF KYRENIA. THINK WHAT CHANGES IT MUST HAVE SEEN.)

Bitter Lemons is no longer a meaningful guide to the physical characteristics of Cypriot life, given that community has been so terribly mauled by civil war and now entirely seperated along ethnic lines. The Greeks are all in the south and the Turks in the north. The quaintness of their backwater existence has also been further deluged by a tsunami of tourist development. Apparently it is far more pronounced on the Greek side.

(ONE OF THE SAVING GRACES OF THE ENTIRE MEDITERRANEAN LANDSCAPE IS THE PREVALENCE OF TREE CROPS. ALTHOUGH CHEMICALS ARE OFTEN NOW USED TO CONTROL THE SURROUNDING VEGETATION, THE TREES ARE A GLORIOUS HABITAT IN THEIR OWN RIGHT. AND OFTEN CHEMICALS ARE NOT USED AND THE GROUND AROUND THEM IS THEN A FLOWER-RICH PARKLAND. I WAS MESMERISED BY THE SLOW-GROWING ANCIENTNESS OF SOME OLIVES. THIS ONE [ABOVE LEFT] WAS PROBABLY AROUND 400-500 YEARS OLD JUDGING BY THE GROWTH RINGS ON JUST ONE SMALL SIDE BRANCH.)

Yet two things resonated deeply on re-reading the book. One, which I had completely overlooked previously, is Durrell’s loving attention to the flowers and trees on Cyprus. (But then how could I not have noticed it? It is, after all, called Bitter Lemons!) We were there during December yet the vegetation was still a powerful part of our own experience.

(MY FAVOURITE TREES WERE PROBABLY THE CAROBS, WHICH HAVE A TENDENCY TO HAVE TWO PRIMARY TRUNKS (POLLARDS PERHAPS?) THAT GROW OUT AND TOPPLE OVER ONLY TO REROOT AND CONTINUE GROWING. THEIR DENSE SHADE WAS IDEAL FOR ROOSTING LITTLE OWLS AND THE CYPRIOT TURKS GATHER THE PODS, ONCE KNOW AS ST JOHN’S BREAD, FROM WHICH THEY MAKE A STRANGE BITTER-SWEET JUICE [PEKMEZI] WHICH THEY HAVE FOR BREAKFAST WITH TAHINI AND CABBAGE. I MUST CONFESS IT REMINDS ME OF MARMITE. THIS INDIVIDUAL, ON THE KARPAS PENINSULA IS REALLY OLD AND HAS PROBABLY BEEN PRODUCING A CROP SINCE THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.)

The second element, which seems such a contradiction of the first, was Durrell’s ability to summon the sheer nihilism of terrorism. It is almost as if he had written the book with our own times in mind. Inter-ethnic strife, war without boundaries or limits, Muslims and Christians – you begin to see how Bitter Lemons speaks so powerfully to our own age. Here, however, the terrorists are all Greek and their victims are either those Cypriots who had collaborated with the island’s political masters, or they are the English overlords themselves. In fact, Durrell’s own life was eventually threatened.

The one false note in the book is Durrell’s half-hearted attempt to dodge the injustice of colonialism. His defence of the imperial government, particularly its governor-general John Harding, seems odd from a writer whose entire oeuvre derived so much from its antagonism to the narrowness and cold-hearted smugness of English public life. Yet, in Bitter Lemons he looks rather reactionary.

In a way, Durrell resolves the dilemma by viewing the politics from the perspective of his Cypriot friends and by stressing the impacts of public terror on private lives, those of his friends and his neighbours. And this is where those flowers and trees start to carry significance.

Botanical imagery is recurrent throughout the book and is most evident in Durrell’s comedic portraits of local Cypriot life or the tavern camaraderie of Bellapaix, but especially in his account of a Greek friend Panos, a schoolteacher from Nicosia. ‘In his memory’, Durrell notes of this tender-hearted scholar and naturalist, ‘he carried a living flower-map of the range, and he knew where best to go for his anemones and cyclamens, his ranunculuses and marigolds. Nor was he ever wrong.’

(DECEMBER WAS NOT A MONTH TO SEE CYPRIOTS FLOWERS AT THEIR BEST BUT WE DID FIND THESE VERY EARLY NARCISSUS. RICHARD MABEY IDENTIFIED THEM AS N. TAZETTA.)

The final fifth of the book is taken up with Durrell’s description of an outing with Panos. It is, in many ways, very typical of the leisure-filled, carefree, pleasure-loving spirit that pervades all the travel writing by Lawrence Durrell. The two men go to inspect a friend’s garden. They have a picnic. They drink wine and smoke cigarettes and savour the very airs of spring: ‘this spring breeze which … am I imagining it?’ says Panos, ‘tastes of lemons, of lemon-blossom.’

Later they collect great basketfuls of flowers and when they are stopped at an army roadblock, Panos is confronted by a young English squady, whose red beret is notably described as ‘gleaming like a cherry among the silver olives.’ The private happens to pass comment on the great pannier of blossoms in the back of Durrell’s car and with that Panos immediately hands him ‘several great bunches of Klepini anemones’.

He made a vague gesture of handing them back, saying: ‘I’m on duty now, sir,’ but I had already let in the clutch and we were rolling down among the trees to the village, leaving him alone with his problem and the smiles of his companions.

There, in a way, you have the whole book: a gift of flowers as a small kindness between people of different race; but flowers also as emblems of the generosity of spirit from which flows all human friendship; and flowers, finally, as the absolute inverse of war. Flowers, as they always have been, are the blessings of peace in Bitter Lemons. All of this has been made so much more poignant and affecting, because right at the start of the chapter, Durrell has already told us that Panos was shot dead by terrorists as he walked out one evening in the town. We are allowed to observe the beauty of his soul, the beauty of his flowers too, from the perspective of his senseless murder.

It is a consummate, masterly piece of controlled writing. It says so much more about the failure of humankind when it resorts to terror than anything written by one of the modern immortals like, say, Martin Amis. It is why I love Durrell’s work. It’s why he is still in print despite that loss of popular acclaim.

———————————-

There is one brief personal postcript to this post: It was Lawrence Durrell’s Bitter Lemons that gave me the title for one of my earliest books. In the first chapter he wrote: ‘We had become, with the approach of night, once more aware of loneliness and time – those two companions without whom no journey can yield us anything.’ For me the claim still holds absolutely true about all travel and all travel writing.

margaret21

/ December 30, 2015It’s very many years since I was a student, and very many years since I read the Alexandria Quartet. Yes, those books were required reading then. Thanks for encouraging me to go back and have another look.

rcannon992

/ December 30, 2015Thanks: Makes me want to read Bitter Lemons! As an adolescent/young man I loved the mysterious sensuality of tha Alexandria Quartet (although I didn’t finish them). So ‘other’ to my then experiance.

Not surprised to hear about the botanical leitmotif given the impact that the fauna and flora of Cyprus had on his younger brother Gerald.

mark cocker

/ January 4, 2016thanks Ray yes, he was almost required reading wasn’t he? But he faded pretty sharply in the 80s and now hardly gets a look in. But I see the public still read him. Many books still in print and doing well. There was clearly a love of nature across the family and, as you say, Gerald’s book on Corfu outlines the extent to which it featured in their lives.

murray marr

/ February 9, 2016Thanks, Mark. I’ve put Bitter Lemons on my reading list.

mark cocker

/ February 9, 2016Glad to know someone else’s shelf of unread books is expanding exactly in the way that mine does Murray

murray marr

/ February 9, 2016Yep. I’ve plenty of those.

Here’s one bought in 1969. The author is some Victorian naturalist who wrote a medium sized volume called The Origin of Species.

Professor Steve Jones, however, made a shrewd observation on such laziness. It’s a rough paraphrase and went: ‘the sort of person who reads Darwin are students of English rather than biology.’

Having been rumbled in this way, I now find I can announce my guilty secret with a kind of perverse authority. However, I’m not sure if the head can held so high regarding all the other books that beckon.

viktor wynd

/ October 11, 2017i have 16 of durrells books on my bookshelf (of course many more by the other one) Alexandrian Quartet is one of the best books i’ve ever read – i must have read it three or four times and will read it again. but i don’t have Bitter Lemons or Prospero’s cell and i haven’t read Reflections. I think i got very stuck on the avignon ones. but will order bitter lemons now

mark cocker

/ October 12, 2017many thanks Wynd and may the book inform your visit to Cyprus this autumn. The other point is well made: Durrell remains doggedly popular with some people, despite the loss of status generally. It is now ‘cooler’ to say you like Gerald rather than big brother Lawrence.